As a graduate student at The Solstice MFA in Creative Writing Program at Pine Manor College, I had the good fortune to sit side-by-side with James Anderson in our workshop group (See James’ full bio below). He was (and is) kind, generous, and smart. Today (Jan. 16, 2018), James celebrates the launch of his second book Lullaby Road.  The early reviews are excellent. The Washington Post Book Worlds says of James, “Exceptional—outstanding in every regard—writing, plot, dialogue, suspense, humor, a vivid sense of place.”

The early reviews are excellent. The Washington Post Book Worlds says of James, “Exceptional—outstanding in every regard—writing, plot, dialogue, suspense, humor, a vivid sense of place.”

I am thrilled that James is guest blogging today. He asks, “Are you an architect or a gardener?” A good question for both writers and non-writers alike.

Take it away James:

Writing In The Dark: Of Architects and Gardeners

I offer, without attribution (I don’t know the source) the observation that there are two kinds of novelists: architects and gardeners.

Architects do a detailed outline of a work before they begin writing; gardeners, by comparison, just begin planting and see what grows and then cultivate and harvest whatever pops up.

Jane Smiley and John Barth are examples of architects; while F. Scott Fitzgerald and Gabriel García Márquez are examples of gardeners.

Both processes produce wonderful novels, though my heart, and my own process, is aligned with gardeners, whose works are more often than not, flawed but somehow, at least to me, more human.

Why do writers write?

Rather than try to answer that question, which has been answered ad infinitum and still remains unanswered, I believe the core motivation, whatever the answers are, can be reduced to either building or exploring.

I was vehemently and roundly chastised by a famous and successful author in a workshop several years ago because the “chronological” or real elapsed time of a scene did not conform to the “literary time” (my term) of the scene.

This particular writer is an architect.

This particular writer is an architect.

She begins with a detailed blueprint and then does elaborate color-coded flow-charts of the scenes, action, characters, motivations, etc. before she writes the first word. Quite simply, my “error” seemed to enrage her which, I admit, both hurt and amused me—and it also pissed me off, a little largely because she used up three times the allotted time allowed for a discussion of each participant’s work, to harangue me—which, for me, seemed to pass in literary time, which is like geological time, only longer.

Dennis Lehane has said that process doesn’t matter.

I agree.

Whatever gets you writing and through the project and works for you is as good as any other. Your worst completed work will always be better than your best, unfinished or abandoned work.

My guess is that architects have fewer abandoned projects because they have already spent a lot of time planning and working through problems.

The gardener just walks out into the field and begins. There might be a vague story lingering somewhere, a setting or a character, a snip of dialogue, or, in my experience, a central image, however indistinct, that carries an emotion, maybe several, inside it. Wherever the gardener begins, it is rarely at the beginning. The gardener doesn’t know the true beginning, or the end, and doesn’t care. The true beginning, middle and end will be revealed, like the plot, in the writing process, one word, one sentence, one paragraph at a time.

The gardener just walks out into the field and begins. There might be a vague story lingering somewhere, a setting or a character, a snip of dialogue, or, in my experience, a central image, however indistinct, that carries an emotion, maybe several, inside it. Wherever the gardener begins, it is rarely at the beginning. The gardener doesn’t know the true beginning, or the end, and doesn’t care. The true beginning, middle and end will be revealed, like the plot, in the writing process, one word, one sentence, one paragraph at a time.

The downside to this process is that it tends to accentuate the organic nature of a novel and thereby necessitates what seem like endless revisions. Writing in the dark involves a lot of trial and error.

My novel (excuse the obviously self-referential) The Never-Open Desert Diner required fourteen major revisions. This was before any actual post rough draft editorial work. To achieve what eventually became a novel of approximately 86,000 words I had to write well over a million words. A lot of that writing never made it into the novel.

Was it worth it?

Yes.

For me, writing a novel is an adventure, an exploration of unknown territory, so there are missteps and detours, all of which are instructive and always fun, even the dead-ends. One of my favorite scenes of my novel occurred because I had written my protagonist into a small bathroom and while I could have deleted it, I chose to deal with the problem in situ. The result was quite a surprise for me and, as I later learned, equally surprising to readers.

My general feeling about being an architect or a gardener, comes down to this: No matter how much you map out a novel in advance, you will probably always discover problems and that can be a very good thing. If you are not surprised, the odds are your reader won’t be either. Great novels, though, are written both ways, and finally it comes down to your own creative nature.

The late novelist John Gardner once said that novelists rarely write the novel they sat down to write. If that is the case, perhaps sitting down and simply holding on for the ride is a good way to go about it. Of course, you will be on that ride loop fourteen times, but you will discover something new each time and what you learn might not always be applicable to the work at hand, though nothing is ever for nothing.

The detours and dead-ends teach you lessons you can use elsewhere—maybe—or just lessons and discoveries about yourself.

But know this, whichever process you choose, pack a lot of perseverance. No matter how long the project takes or how much work, the adventure is always worth it, even if you find yourself broken down on the shoulder of an uncharted isolated road unable to remember where you are headed. When this happens (and it will) light up an imaginary cigarette and watch the sunset and get up in the morning and start walking.

***

More about James:

James Anderson was born in Seattle and raised in Oregon and the Pacific Northwest. He is a graduate of Reed College in Portland, Oregon, and received his Master’s Degree in Creative Writing from Pine Manor College in Boston. For many years he worked in book publishing. Other jobs have included logging, commercial fishing and, briefly, truck driver. He currently divides his time between Ashland, Oregon, and the Four Corners region of the American Southwest.

You can follow James on Facebook and Twitter or drop by his website to say hello.

Writing has laws of perspective, of light and shade just as painting does, or music. If you are born knowing them, fine. If not, learn them. Then rearrange the rules to suit yourself.

Truman Capote

***

Please consider putting James Anderson’s Lullaby Road on your to-read list. Click HERE to find it on Amazon.

***

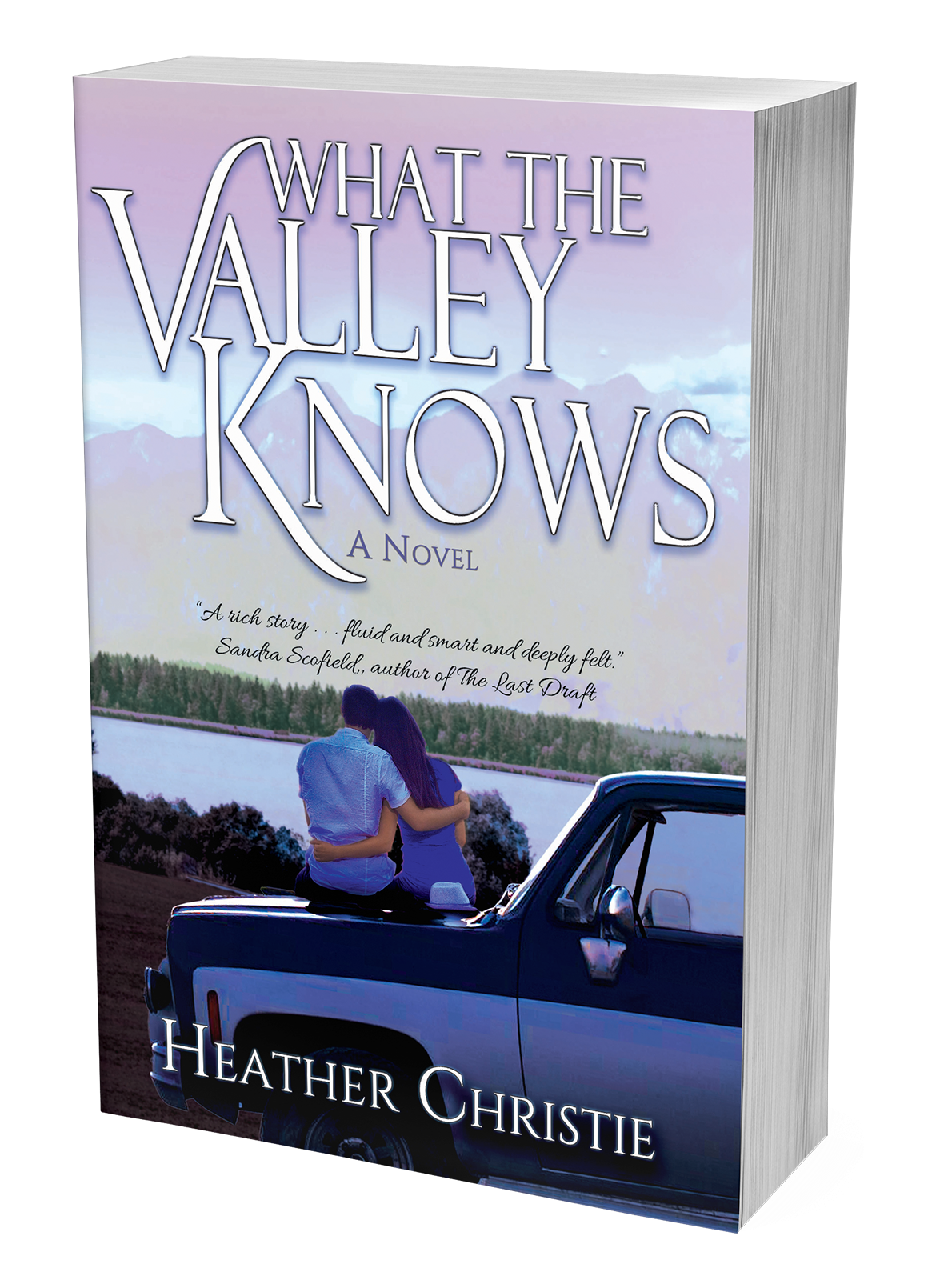

As you might have guessed, I am a plan-every-detail architectural type of writer. I’ve been sowing lots of WHAT THE VALLEY KNOWS seeds. The official launch is January 25, 2018! I hope you’ll help me make it grow. Purchase HERE.

xoxo,

Heather

Gardener, for sure. Great inspiration, James. You keep good company, Heather.